‘Soundings’ is a retrospective of mixed media works created over a decade by Rosemary Holcroft, painter and Royal College of Art graduate. The paintings trace an ongoing and determined philosophical investigation, embodying polarities of thinking and feeling, chaos and order, truth and mystery. Continue reading

Category Archives: Exhibition Reviews

Valley of Lights

Valley of Lights was a series of three parade-centred events held in the Upper Calder Valley towns of Todmorden, Hebden Bridge and Mytholmroyd coinciding with the Christmas Lights switch-on. The aim was to give the towns a boost after the devastating floods of Summer 2012, and to celebrate the Valley’s recovery. So yes, it was about showing everyone that the towns are very much open for business, and retailers and stallholders were open to delight shoppers. But it was about something much more. I think its real power was in strengthening the community through a collective reflection, healing, and moving on together. It did this in three ways – through bringing people together to physically make things; through the healing power of collective storytelling; and through a performative connecting of the three towns.

Valley of Lights was a series of three parade-centred events held in the Upper Calder Valley towns of Todmorden, Hebden Bridge and Mytholmroyd coinciding with the Christmas Lights switch-on. The aim was to give the towns a boost after the devastating floods of Summer 2012, and to celebrate the Valley’s recovery. So yes, it was about showing everyone that the towns are very much open for business, and retailers and stallholders were open to delight shoppers. But it was about something much more. I think its real power was in strengthening the community through a collective reflection, healing, and moving on together. It did this in three ways – through bringing people together to physically make things; through the healing power of collective storytelling; and through a performative connecting of the three towns.

1. Making things

Handmade Parade has been delighting the communities around Hebden Bridge since 2008. It is a community parade with three simple rules – no logos, no motorised vehicles, and everything made by hand. Community workshops are held prior to each parade in which people are invited to make their costumes, or help to make large scale puppets which will be carried. As one of the volunteer helpers in their first year, I know that this involves a lot of hands-on messiness, up to your elbows in papier mache, paint, glue and cardboard. For Valley of Lights, participants made lanterns in symbolic forms representing the three towns, with higgledy piggledy town houses out in force. But I think the strength of this activity is the collective making of things – coming together to work materials with the hands and craft forms. This is a timeless community activity, whether it be basket weaving, coiling pots – or making lanterns. There is something about working with the hands that enhances quality of conversation, and indeed that has a language of its own.

2. Collective Storytelling

These handcrafted puppets and costumes then take to the streets, together with handmade music from the valley’s home-grown samba and street bands. The parade is hugely celebratory with the crowds clearly delighting in the spectacle. But it is about more than just marching and looking. The parade sets into play a narrative which is developed through the parade finale. For Valley of Lights, the fire finale told the story of the great floods of 2012, through large lantern puppets of town houses and landmarks such as Stoodley Pike, Hebden’s bridge, and the Mytholmroyd clock tower. Clouds appeared and danced over the towns as the flood waters advanced. A huge shadow puppet display showed people arriving to rebuild the towns (I think – being short I was struggling to see, so if anyone can fill me in on this I’d be grateful!). Finally, a dazzling display of firework fountains and fire dancers celebrated the recovery and the power of community. As a participant I felt that I was taking part in a ritual healing retelling of our story, and a passing of that story into myth – so that we can move on with light and hope.

3. Connecting the three towns

On the middle event in Hebden Bridge, the finale was followed by the arrival of 200 cyclists who were cycling from Todmorden, via Hebden, and then onward to Mytholmroyd. They made quite an impression with bikes and bodies blinged-up with LEDs, and bells merrily ringing – a river of light and sound running through the valley. For me, this was a performative act (an action that does what it says). In the very act of cycling between the three towns, they were making the connection between them. The meaning was in the cycling. As a spectator, this was literally moving, bringing tears as well as smiles and cheers. I found it profoundly affecting.

As a beautifully conceived celebration, recovery, stimulus and remarkable demonstration of the creativity and strength of the people of the Upper Calder Valley, it couldn’t have been better. Huge thanks to Valley of Lights organisers and Handmade Parade for giving us all something to be proud of, and some sparkling memories.

and it all comes down to this …

Beautiful piece of immersive theatre at stage@leeds last night. David Shearing’s and it all comes down to this … made my throat ache with the beauty of it. It offered nostalgia, melancholia, and a deep reflective sense of the expanse of time and space. David’s voice invites you to explore a world both inside and outself yourself, where text folds in on itself, becomes form, and takes flight. Like being led into a lucid dream. A real gift.

These Associations – Tino Sehgal

Arriving at the Tate Modern, I look down into the Turbine Hall. There is a group of people scuttling around like ants or atoms, avoiding each other, in constant motion. The ‘milling’ seems to be busy, without purpose. Bodies walk quickly in random movements, individuals ‘bunched’ into a group, related to each other by their inexplicable behaviour. I shrug, and go and look at some art.

Later, I exit into the Turbine Hall. Several rows of people jog past, down the length of the hall. I follow them at a more sober pace (although I feel a strange urge to jog after them). I stop as they turn and start to run back towards me. I want to feel the current of air as they pass, to feel the strangeness of being amongst these purposeful bodies. I’m a spectator, but a ‘sensing’ one – the spectacle is an embodied experience.

A figure breaks out of the group and runs with purpose towards me. She is breathing heavily, and sweat shines on her face. She smiles, makes eye contact, and talks breathlessly about the place she calls home. A body, a living, breathing, sweating body confronts me with the intimate details of a lived life – the place she calls ‘home’. I find myself wondering what place I would call home. I’m plunged into intimacy with a complete stranger, and yet she seems not strange any more. Her look is warm, her smile engaging.

Suddenly, her face goes blank. She turns and joins the mass of bodies now walking past; is swallowed up by their glassy stares. I am alienated, reduced to observer.

This experience is repeated several times as the Body of bodies slows to a shuffle. As it advances – slowly – the lights switch off one by one. By the time they reach me, we are in darkness. The feeling is undead, uncanny.

The repeated alienation juxtaposed with intimate personal encounter makes me reflect on the ‘alienation of the other‘ – the amorphous Body that we don’t know personally – whether they be ‘bankers’ or ‘hoodies’. A body that emerges from the ‘Body’, with real lungs and sweat glands to tell me their most personal stories about their homes or mothers, can challenge that alienation. A Body of strangers can move with purpose or seeming randomness – but that one individual can suddenly spin out and confront me reminds me that the ‘Body’ is made up of people who share the humanity of being a physical body in space, with purposes and passions. What makes the ‘Body’ behave the way it does when it is a collection of individuals? It is probably a function of some rules the individuals have agreed, and affected by the responses of the participants that they encounter in the ‘performance.’ Sounds kind of familiar.

‘These Associations’ is an artwork created by Tino Sehgal and can be found in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern until 28 October 2012.

Mike Holcroft New Work

Mike Holcroft has an exhibition of new work at Water Street Gallery. I’ve written a review here.

Trip to Newcastle

We visited the Turner prize 2011 show at the Baltic, Newcastle last weekend. Loved it. I can’t decide between the exuberant wallpaper and bath bombs, or Shaw’s sublimely morose paintings. Glad I’m not on the judging panel.

We visited the Turner prize 2011 show at the Baltic, Newcastle last weekend. Loved it. I can’t decide between the exuberant wallpaper and bath bombs, or Shaw’s sublimely morose paintings. Glad I’m not on the judging panel.

Walking into Karla Black’s installation, we are faced with sheets of polythene liberally smeared with paint which has dried and flaked off, the flakes of colour piled up on the floor. It is like walking into a magical grotto. Glimpsed through these painterly curtains, you can see the sculptural mounds and caves of what looks like crumpled wallpaper liberally coloured with bath bombs (judging by the number of bath bombs lying around). The effect is unexpectedly joyous, stimulating a bubble of sudden giddiness. I want to get down on my hands and knees and scribble. I want to put my hands in the piles of pastel dust and smear them around the floor. Most of all, I want to PLAY. My husband was affected similarly, he thought it was great fun.

By contrast, George Shaw’s paintings inspire a more sombre emotion. The paintings themselves are sublime, with their perfect composition and rendering of sub-urban Tile Hill in Coventry. The enamel paint gives them a soft shiny gloss that makes the surface as perfect as china. But the paintings seem to hint at loss, whether loss of people, places or a lost childhood it is up to us to interpret. There is a good review with pictures on the Guardian website.

Mike Holcroft ‘Flowers ….. plants & other stories’

This exhibition of Mike Holcroft’s new work has three elements: vibrantly coloured flower paintings; a series of ‘vanitas’ style still lifes; and a series of flower drawings on paper. (Click the above link to see images of his work) Continue reading

Mary Kelly: Projects, 1973 – 2010

Yesterday I visited Mary Kelly’s retrospective at the Whitworth in Manchester. Kelly’s work uses text and personal narrative to explore themes of identity, memory and sexuality. Her more recent work carves words and scraps of narrative into built structures, using light or mirrors to enable you to read the words. Her earlier work collected objects and texts to re-present memories and stories.

Yesterday I visited Mary Kelly’s retrospective at the Whitworth in Manchester. Kelly’s work uses text and personal narrative to explore themes of identity, memory and sexuality. Her more recent work carves words and scraps of narrative into built structures, using light or mirrors to enable you to read the words. Her earlier work collected objects and texts to re-present memories and stories.

The work that most held my attention was the iconic Post-Partum Document 1973-79. This piece filled an entire gallery, and was a six-year exploration of her relationship with her son, from birth to starting school. Considering its age, the work looked as pristine as if it had been made yesterday. I suspect it may have been carefully remounted and presented. The first part consisted of tiny wool vests, annotated with diagrams and text and presented in Perspex units. The next section showed a month’s worth of stained nappy liners with analysis of the food consumed by the infant, presented in Perspex. Walking along the 31 units, all meticulously dated, I started to feel some of the monotony of feeding and changing, hour after hour, day after day, along with the paranoid concern about whether the baby is getting the right nutrition or eating the right amount. The boredom and responsibility of motherhood.

Next up was a set of ‘Analysed utterances and related speech events’, using printing blocks and typewritten text to recreate the first words spoken by the child, along with the context of the conversation and an analysis of the ‘purpose’ of the words spoken (existence, non-existence, absence, etc). Throughout Post-Partum document, Kelly uses three voices – the child, her own, and that of the ‘analytic observer’. ‘Transitional Objects, Diary and Diagram’ 1976 presented imprints of the child’s body in clay along with scraps of cotton and diary extracts. However, it was the ‘Classified Specimens, Proportional Diagrams, Statistical Tables, Research and Index’ 1977 that I found mesmerising. Objects collected by the child (often beautiful in their own right, such as moths and beetles) were presented alongside a diary of the child’s exploration of genitals and gender recounted through scraps of dialogue. Finally, the introduction of the child’s schooling was presented on slates, with reproduction of the child’s first letters; the artists’ account of the trials of finding appropriate nursery and school; and the way letters are taught (‘a’ is for apple)

The pieces follow the path of child development theories of Freud, Winnicott and Klein, which Kelly would clearly have been aware of. I found myself wondering how reliable a narrator she was, yet at the time this piece was made I’m guessing the artist may not have had the post-modern ‘knowingness’ that we have now come to expect. I was interested in how the traces of childhood were ‘captured’ in a completely different way to snapshots, using physical traces (the faecal stains and clothing), words (the child’s and artist’s) and other ephemera (the collected objects). As an observer I didn’t feel at all voyeuristic, and yet I did feel I had shared an important part of the artist’s life in some way. This was achieved with the ‘distancing’ of the museum exhibit alongside the intimacy of the personal diary extract.

I feel privileged to have seen this piece in its entirety, as there is no way it can be effectively experienced in print form. It also made me wonder whether her work had influenced other artists who are favourites of mine such as Annette Messager and Sophie Calle, as Kelly’s work was highly influential in the development of conceptual and feminist art.

‘Mary Kelly: Projects 1973-2010’ is on at the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester from 19 Feb to 12 June 2011.

You can see some images of Post-Partum Document on this website.

David Gledhill and Corin Sworn at Castlefield Gallery

Last night, a friend and I made the effort to trawl out to Manchester to Castlefield Gallery to see David Gledhill and Corin Swornin conversation. Both artists use found snapshot photographs in their work. It was fascinating hearing how they had reconstructed a narrative based on images which had been discarded. David had come across a photo album that had been found in a flea market, and Corin had found a skip full of slides.

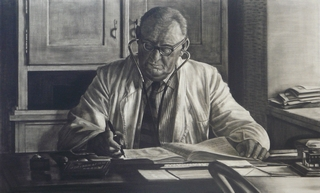

From the photograph album, which Doctor Munscheid had presented to his daughter on the occasion of her wedding, David Gledhill created a series of paintings in soft sepia hues. He aimed to recreate the ‘idealism’ that he saw in the photographs which were taken in East Germany between 1951 and 1962. In them he saw a family surviving a regime change by carrying on (or appearing to carry on) as normal. I reflected that this is a feature typical of family snapshots – they ignore the socio/political and industrial context. There was some discussion about how snapshots are carefully framed and posed performances, and how the photographer wanted to portray an idealised family. Yet there were uncanny aspects in the images. One showed the Doctor sitting at his desk writing, his stethoscope indicating his profession. And yet the stethoscope was in his ears. Why? Something that struck me in David’s talk was his keen interest in the subjects of his paintings. As he said, he liked to paint subjects that he is fascinated by. He had done a lot of research into the time, place, and politics of the community represented. It brought home the fact that by painting snapshots, you also draw attention to the context in which they were taken.

From the photograph album, which Doctor Munscheid had presented to his daughter on the occasion of her wedding, David Gledhill created a series of paintings in soft sepia hues. He aimed to recreate the ‘idealism’ that he saw in the photographs which were taken in East Germany between 1951 and 1962. In them he saw a family surviving a regime change by carrying on (or appearing to carry on) as normal. I reflected that this is a feature typical of family snapshots – they ignore the socio/political and industrial context. There was some discussion about how snapshots are carefully framed and posed performances, and how the photographer wanted to portray an idealised family. Yet there were uncanny aspects in the images. One showed the Doctor sitting at his desk writing, his stethoscope indicating his profession. And yet the stethoscope was in his ears. Why? Something that struck me in David’s talk was his keen interest in the subjects of his paintings. As he said, he liked to paint subjects that he is fascinated by. He had done a lot of research into the time, place, and politics of the community represented. It brought home the fact that by painting snapshots, you also draw attention to the context in which they were taken.

Corin Sworn created an installation of slide projectors displaying a selection of the slides she’d found. There was a small red diary with notes and ‘to-do’ lists. A vase of flowers in one corner had a slide projector pointed towards it, casting a shadow of the flowers onto the wall. For me, this raised questions of signifier and signified, and also referenced the myth of the birth of painting, where a girl traced the profile of her lover from his shadowed profile on the wall. There was a tape cassette player playing a commentary read out by the artist from a set of notes that were also available to read. Some of the written notes had been crossed out, and were not included in the audio commentary but we could still read them. Corin was interested in the slides as images of the past. She was interested in how they conjure up nostalgia, and its function socially. While she had created a loose narrative, she wasn’t looking for an ‘objective’ position or doing research. She was thinking about the viewer, and how they might try to make sense of the works. She chose to use different subjective viewpoints, many of which she selected from texts including theory and poetry. She was tapping into the history of bringing text into the gallery, and the way that removed the need for an object as art. For her, the word itself has a materiality in its tone and texture. I experienced her piece in a fragmented and dream-like way. Words from the spoken commentary drifted into my consciousness as I was looking at the images. You can’t view both projections at once, so viewing them is a fragmented experience. I tried to construct my own narrative, piecing things together from the diary, the images and the commentary. But I couldn’t make it make sense; coherence evaded me. I liked that.

Corin Sworn created an installation of slide projectors displaying a selection of the slides she’d found. There was a small red diary with notes and ‘to-do’ lists. A vase of flowers in one corner had a slide projector pointed towards it, casting a shadow of the flowers onto the wall. For me, this raised questions of signifier and signified, and also referenced the myth of the birth of painting, where a girl traced the profile of her lover from his shadowed profile on the wall. There was a tape cassette player playing a commentary read out by the artist from a set of notes that were also available to read. Some of the written notes had been crossed out, and were not included in the audio commentary but we could still read them. Corin was interested in the slides as images of the past. She was interested in how they conjure up nostalgia, and its function socially. While she had created a loose narrative, she wasn’t looking for an ‘objective’ position or doing research. She was thinking about the viewer, and how they might try to make sense of the works. She chose to use different subjective viewpoints, many of which she selected from texts including theory and poetry. She was tapping into the history of bringing text into the gallery, and the way that removed the need for an object as art. For her, the word itself has a materiality in its tone and texture. I experienced her piece in a fragmented and dream-like way. Words from the spoken commentary drifted into my consciousness as I was looking at the images. You can’t view both projections at once, so viewing them is a fragmented experience. I tried to construct my own narrative, piecing things together from the diary, the images and the commentary. But I couldn’t make it make sense; coherence evaded me. I liked that.

With both artists, I was interested in why they chose to take discarded images and reconstruct something from them. I was interested in the human impulse which their work represents which makes us feel that such personal images which have been simply chucked away have an almost unbearable poignancy. That impulse to rescue them, lavish attention on them and reconstruct some sort of narrative (however fragmented) took me back to something Roland Barthes said about photography being an attempt to cheat death. Perhaps if we can bring these lives back to life in some way, then our own lives with all their richness and complexity won’t simply vanish and become meaningless once we die. How many of us can really bear the idea that when the lights go out for the last time, all the things we value, strive for and care about become someone else’s problem to be chucked in a skip?

Christian Mieves ‘On the Beach’

Thoroughly enjoyed Christian Mieves’ exhibition of paintings that evoked and explored the beach and geographical and political associations with the beach as a ‘boundary’ land. The colour palette used is consistent throughout the works – pale greeny-blues and blue-greens, dull ochre rather than sandy-gold. These ‘off’ colours create a sense of dimness or distance, giving a sense of age, dim memory or dull pain. The paintings are constructed vigorously, with bold brushstrokes defining a limb or the strut of a boat. The style reminded me vaguely of Bomberg in the confidence of the brushstrokes, but the style was looser, and the paint thinner. Mostly you can see the surface of the canvas, wood panel, tiles, or aluminium – he’s experimental with types of surface. He’s also not afraid to vary the scale. Some filled a gallery wall, several feet wide. Others, such as this one, were tiny – only 11×7.5cm on mdf. I loved these paintings, the drips and pencil marks and bits of bare canvas. They weren’t afraid to show their making, and were highly desirable objects. Some of them explored the site of the beach as a landing place, and not always a successful one. Two hinted at shipwrecked hulls, and my favourite was of a figure draped over the bow of a boat, listless, exhausted, or dead. The exhibition is on at South Square Gallery near Bradford until 30th November 2009.