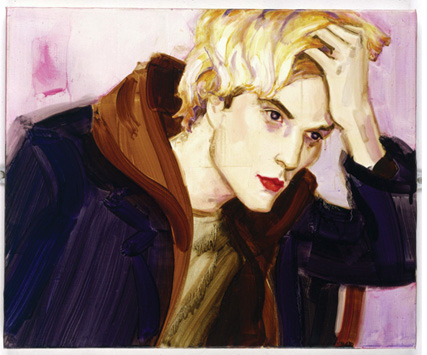

Craig (1997) (Image from Whitechapel Gallery)

“Oh my God, I didn’t realise they were so SMALL!”

This was my first startled reaction on entering Gallery 8 in the Whitechapel Gallery, London. I’d seen many reproductions of Elizabeth Peyton’s work, but none in the flesh. The scale took me totally by surprise. Most of the works are not much bigger than an A4 piece of paper, and most are on thick slabs of what looks like MDF, making them quite chunky and substantial objects despite their small scale.

The size meant you got right up close to them, like you would to a photograph. Once there, these paintings pack a real punch. It’s not just the dense bursts of colour – which have been aptly described as ‘jewelled’ by many commentators. It’s also the dreamy beauty of her subjects. She describes their features in loving detail – particularly the eyes, and her trademark red mouths. The rest of the figures are dealt with in a much looser fashion with a few dabs of paint. And fashion is an apt word here. Many of her drawings and paintings resemble fashion illustration, with fine noses and hands carefully outlined and long legs stylistically posed. Her paintings seem to owe much to drawing, despite the painterly brushstrokes and washy glazes which are allowed to run into each other.

The small scale lends her paintings intimacy, but her subjects seem absorbed in their inner world, unaware of a viewer’s presence. The paintings share with their source photographic material a sense of voyeurism – we are peeking in at someone’s more private and reflective moments. In ‘Nick Reading Moby Dick’ (2003), a young man wearing a bright red jacket with red-white-blue pin striped shirt has a book open on his knee. He does not appear to be reading at all – rather, he is staring into space, his bright blue eyes depicted in fine detail with the dark outer ring of the iris, and salmon-pink eyelids. He seems composed, dreamy, lost in thought. The bright red of his jacket is enhanced by the dark greens and browns of the parkland surrounding him, with a flash of lime green grass glimpsed through trees.

Some people I felt I’d met before, such as the blonde girl in ‘Liz and Diana’ (2006) where the pinkish tip of the girl’s nose is somehow familiar and totally human. As she sits curled up, writing in a book on her lap, I feel I must have seen her often in a library somewhere.

I came across one or two on a much larger scale (we are still only talking 2 or 3 feet here!) and in contrast to the tiny portraits I had become used to, I found these strangely overwhelming and much less intimate. They seemed to dominate me, and I didn’t like the feeling much. I also felt that the more recent seated portraits taken from life rather than from a photographic source strangely lacked life, appearing flatter, packing less colour and emotional charge, and seeming less real somehow than her photo-sourced images. For me, this calls into question one of those ‘truisms’ I am so often faced with that the only ‘real’ paintings are those that are painted from life.

Peyton somehow manages to make all her subjects look beautiful, with their finely defined noses and upper lips, incredibly detailed eyes and eyelashes, and their flowing hair. After spending a couple of hours greedily drinking them in, I left the gallery only to find that everyone I saw – and I mean everyone – looked beautiful. So beautiful that I wanted to draw the faces that I saw on the tube, to capture their individuality and their beauty. Now that is a gift.

Live Forever is on at the Whitechapel Gallery in London from 9 July until 20 September 2009.

(Review also posted on a-n Interface)

this is beautiful Crole and you’ve given such a lovely review!

ronell

sorry for the horrible misspelling of your name! xx